Even before the Declaration of Independence the Navy raised its flag on the first American warship, the Alfred, on December 3, 1775 and conducted its first Marine raids on New Providence, Bahamas on March 3, 1776. Since that time it has been the single greatest guarantor of American sovereignty and Edward L. Beach has been one of its greatest chroniclers.

In this story of disaster and heroism his father was the captain of the ship attacked, not by a declared enemy but, by an overwhelming force of nature. There had been such attacks before and others have followed and the threats from our enemies may diminish long before those from the sea. What matters in each case is how the adversary is met. The men of the USS Memphis, including Commander Beach, stood by their stations and acquitted themselves well. The next generation, also a Commander Beach, has related the story with an eloquence worthy of their service.

USS Wateree (1864-1868)Beached at Arica, Chile, 430 yards above the usual high water mark, after she was deposited there by a tidal wave on 13 August 1868. Her iron hull was reasonably intact, but salvage was not economical, and she was sold where she lay. Courtesy of Murray Greene Day.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

USS Wateree, a 1173-ton Sassacus class “double-ender” steam gunboat, was built at Chester, Pennsylvania and was constructed with an iron hull. Commissioned in January 1864, Wateree was sent around Cape Horn to the Pacific, arriving at San Francisco, California, for post-voyage repairs in November 1864. From early 1865 until mid-1868, the gunboat patrolled along the west coasts of Central and South America as a unit of the South Atlantic Squadron.

America (Peruvian Warship)Beached and partially dismasted at Arica, Chile, following the 13 August 1868 tidal wave that washed her and other vessels ashore. Photographed from the seaward side. Ship in the distance, beyond America’s bow, is USS Wateree. This photograph was received from Captain Dudley W. Knox in 1934. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

On August 13, 1868, while she was at the Port of Arica, Peru (later part of Chile), a huge tidal wave struck the anchorage, breaking several ships loose from their anchors and casting them ashore. Wateree was carried nearly five-hundred yards inland, where she was deposited relatively intact. However, refloating and repairing her would have been impossibly expensive, so she was sold where she lay in November 1868. Reportedly, her hulk was subsequently employed as an inn.

USS Tennessee, first of a class of four 14,500 ton armored cruisers, was built at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was commissioned in July 1906 and in November of that year escorted President Theodore Roosevelt when he voyaged to Panama to visit the great canal then under construction. She went to the Pacific later in 1907, remaining for two and a half years as a unit of the powerful armored cruiser squadron then serving in that region.

USS Tennessee (Armored Cruiser # 10)Coaling ship at Honolulu, Hawaii, circa 1909-1910. Three other armored cruisers are visible in the offshore distance. Collection of Harry Gilfillan. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

On her next assignment, Tennessee carried President William Howard Taft on an inspection of Panama Canal progress. She operated in the western Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico areas during the rest of 1910 and the first months of 1911. The big cruiser steamed to the eastern Mediterranean, where she protected American interests and transported refugees during the Middle Eastern turmoil that accompanied the First Balkan War. Upon returning home in May 1913, Tennessee served with the Atlantic Fleet.

USS Tennessee (Armored Cruiser # 10)Crew members carrying stores onto the ship’s boat deck, probably at Alexandria, Egypt, circa late 1914 or early 1915. Ship alongside (at right) may be USS Vulcan (Collier # 5). Collection of Earl P. Crandall. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

In August 1914 Tennessee returned to the Mediterranean, where she conducted humanitarian missions and otherwise “showed the flag” as the First World War spread through Europe and into the Turkish empire. Back in the U.S. by August 1915, she carried Marines to Haiti, and from then until February 1916 was actively involved the effort to establish order in that strife-torn nation.

Late in the May 1916 she was renamed Memphis, allowing reassignment of her original name to a planned new battleship. During the early summer the cruiser took Marine reinforcements to the Dominican Republic, also suffering from revolutionary violence.

USS Castine (Gunboat # 6) Photograph autographed by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN, circa the later 1950s or early 1960s. He served in Castine while commanding the Atlantic Fleet Submarine Flotilla between 20 May 1912 and 30 March 1913. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

At three in the afternoon of 29 August 1916, the 14,500-ton armored cruiser Memphis and the 1177-ton gunboat Castine were riding gently, anchored in the open roadstead off Santo Domingo, capital city of the Dominican Republic. Far away somewhere in the depths of the Atlantic Ocean or Caribbean Sea, a seismic event had already generated a powerful tidal wave. Castine would barely escape its effects, while the other would be driven ashore a complete wreck. More than forty men would lose their lives.

USS Memphis (Armored Cruiser # 10)Wrecked at Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where she was thrown ashore by tidal waves on the afternoon of 29 August 1916. This view probably was taken early on 30 August, as the ship appears to be abandoned. Note the anchor chain running seaward from her starboard bow. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Perhaps twenty minutes later, Memphis’ Executive Officer was troubled by the “looks of the sea” and at about half past three Captain Edward L. Beach, the cruiser’s Commanding Officer, ordered steam power increased enough to allow his ship to leave the anchorage. Previous experience had demonstrated that this could be done in about forty minutes. Waves began breaking ashore and, since Memphis was now rolling too much to recover boats in the water, two of hers were sent out to sea, soon to be followed by one of Castine’s. Shortly afterwards, when a large wave was seen on the horizon, both ships began to prepare for heavy weather. This laborious work was greatly hindered by violent rolling and pitching as waves rapidly became larger and then immense.

USS Memphis (Armored Cruiser # 10)Wrecked at Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where she was thrown ashore by tidal waves on the afternoon of 29 August 1916. This view probably was taken early on 30 August, as the ship appears to be abandoned. Note the lines running between the ship’s superstructure and the shore. Photographed by the local U.S. Consul, Carl M.J. von Zeilinski. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

The effort to get steam up on Memphis suffered even more, with the problem becoming worse as water began to flow over her decks and enter through ventilators, incompletely closed gunports, and even her four tall smokestacks. As a result, when the main waves reached the anchorage about half-past four, Memphis did not have enough steam available to run her engines properly. She dragged her anchor, all the while battering her hull against the bottom, normally some twenty-five feet below her keel. At about five PM she went hard aground near Santo Domingo’s rocky coastal cliffs.

Castine, meanwhile, had gotten clear of the anchorage, following a heroic effort that left her badly battered and barely seaworthy. A motor launch, erroneously sent out of port with much of Memphis’ recreation party embarked, had foundered in the tremendous breakers, leaving twenty-five men dead. Another eight Sailors were lost when the three boats sent to sea sank or were wrecked attempting to reach shore after dark. Ten more were fatally injured on board Memphis, either by being washed overboard or from burns and steam inhalation as the ship’s powerplant broke apart during her ordeal.

USS Memphis (Armored Cruiser # 10) Wrecked at Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, where she was thrown ashore by tidal waves on the afternoon of 29 August 1916. This view probably was taken early on 30 August, as the ship appears to be abandoned. Note the U.S. Ensign hanging from the ship’s stern where the flagstaff had broken away. The top of her rudder and propeller is also visible. Photographed by the local U.S. Consul, Carl M.J. von Zeilinski.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

The big cruiser’s remaining officers and men, many of them badly injured, were brought ashore by ship to shore lines, hastily rigged by U.S. Marines, Navy personnel and local residents. USS Memphis, so thoroughly damaged as to be not worth refloating, remained just off Santo Domingo’s shoreline for many years, a monument to a sudden tsunami, one of nature’s most unforeseeable and powerful forces.

Claud Ashton Jones was born on 7 October 1885 was appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1903 and graduated with the Class of 1906. He served in the battleships Indiana and New Jersey during the next three years and received his commission as an Ensign in 1908. Between 1909 and 1915, Jones was assigned to the training ship Severn and the armored cruiser North Carolina, received post-graduate engineering education at the Naval Academy and Harvard University, and served in the battleships Ohio, New York and North Dakota. He was promoted to Lieutenant (Junior Grade) in 1911 and Lieutenant in 1914.

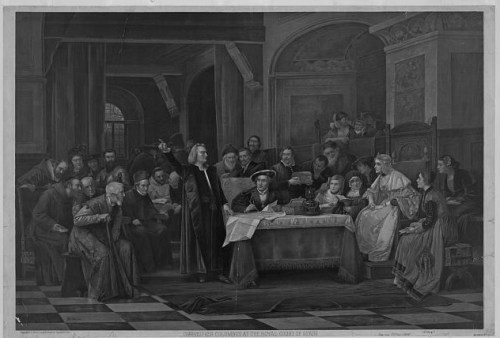

Commander Claud A. Jones, USN Receives the Medal of Honor from President Herbert Hoover, in ceremonies at the White House, 1 August 1932.

Cdr. Jones’ wife and son are partially visible behind him and the President.

Captain Walter N. Vernou, Presidential Naval Aide, is at right. In the left center is Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams. At the extreme left are Rear Admiral Samuel M. Robinson, Chief of the Bureau of Engineering; Captain Harold G. Bowen, Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Engineering (partially visible); and Captain Harold Stark, Aide to the Secretary of the Navy (partially visible). Commander Jones received the Medal for heroism on board USS Memphis (Armored Cruiser # 10) when she was wrecked on 29 August 1916. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Late in 1915 Lieutenant Jones reported for duty as Engineer Officer of the armored cruiser Tennessee. He was severely injured when she was wrecked by a tsunami on 29 August 1916. Many years later, in recognition of his heroic conduct in rescuing crewmen from the dying ship’s steam-filled engineering spaces, then-Commander Jones was awarded the Medal of Honor. After recovering from his ordeal, he served ashore until after the end of World War I.

Lieutenant Commander Jones was designated as a specialist engineering duty officer in 1918 and in 1920-1921, in the rank of Commander, was Engineer Officer of the new battleship Tennessee. During the 1920s and into the early 1930s he had two Navy Department tours with the Bureau of Engineering, served in Europe as an Assistant Naval attaché and was senior engineering officer with the Battle Fleet. He was promoted to Captain in 1933, while again on duty with the Bureau of Engineering, and was Assistant Chief of that Bureau in 1935-1936. Captain Jones had machinery and materiel inspection assignments for the rest of the decade, then returned to Washington, D.C., to serve as Head of the Shipbuilding Division of the Bureau of Ships. As a Rear Admiral, he was the Bureau’s Assistant Chief and, for much of World War II, Assistant Chief of Procurement and Material. He became Director of the Naval Experiment Station at Annapolis, Maryland, from September 1944 until nearly the end of 1945. Retired in June 1946, Rear Admiral Claud A. Jones died at Charleston, West Virginia, on 8 August 1948.

Medal of Honor citation of Commander Claud A. Jones (as printed in the official publication “Medal of Honor, 1861-1949, The Navy”, pages 106 & 107):

“For extraordinary heroism in the line of his profession as a senior engineer officer on board the U.S.S. Memphis, at a time when the vessel was suffering total destruction from a hurricane while anchored off Santo Domingo City, 29 August 1916. Lieutenant Jones did everything possible to get the engines and boilers ready, and if the elements that burst upon the vessel had delayed for a few minutes, the engines would have saved the vessel. With boilers and steam pipes bursting about him in clouds of scalding steam, with thousands of tons of water coming down upon him and in almost total darkness, Lieutenant Jones nobly remained at his post as long as the engines would turn over, exhibiting the most supreme unselfish heroism which inspired the officers and men who were with him. When the boilers exploded, Lieutenant Jones, accompanied by two of his shipmates, rushed into the firerooms and drove the men there out, dragging some, carrying others to the engine room, where there was air to be breathed instead of steam. Lieutenant Jones’ action on this occasion was above and beyond the call of duty.”